Legendary Cartoonist Ben Katchor on the Agony of Creativity

On the 25th anniversary of his first graphic novel, the comic-strip genius opens up about doing the only job he ever wanted.

![]() I became Ben Katchor’s editor in 2005, when I was working at Metropolis, the design magazine in New York that, until very recently, printed his comic strip on its back page every month. He would arrive at our office on West 23rd Street on the day of his deadline carrying his latest panels, drawn in ink and colored in gouache, protectively sandwiched between a thin foam board and a sheet of vellum. He was a MacArthur genius, and I was a 30-something who enjoyed sweating over correctly placing commas, which was about the level of editing I did on his strips. I looked forward to those handoffs and to the brief conversations I’d have with Ben, whose plaintive, New York–inflected tone was described in a New Yorker profile as ‘a voice emanating from a Lower East Side automat.’

I became Ben Katchor’s editor in 2005, when I was working at Metropolis, the design magazine in New York that, until very recently, printed his comic strip on its back page every month. He would arrive at our office on West 23rd Street on the day of his deadline carrying his latest panels, drawn in ink and colored in gouache, protectively sandwiched between a thin foam board and a sheet of vellum. He was a MacArthur genius, and I was a 30-something who enjoyed sweating over correctly placing commas, which was about the level of editing I did on his strips. I looked forward to those handoffs and to the brief conversations I’d have with Ben, whose plaintive, New York–inflected tone was described in a New Yorker profile as ‘a voice emanating from a Lower East Side automat.’

Then, one day, Ben’s visits to the magazine dropped off. He’d started drawing his strips on a graphic tablet, and they were delivered by email instead. I was slightly devastated, and it struck me as an odd move for someone whose primary protagonist — Julius Knipl, real estate photographer — forlornly meditates on the disappearance of urban landmarks, true craftsmanship, and the grand movie theaters. Knipl himself navigates a kind of bygone Lower East Side, where you could get a cold borscht at a diner before bunking down at a nearby flophouse. How could someone who chronicles Knipl’s world swap an ink nib for a stylus?

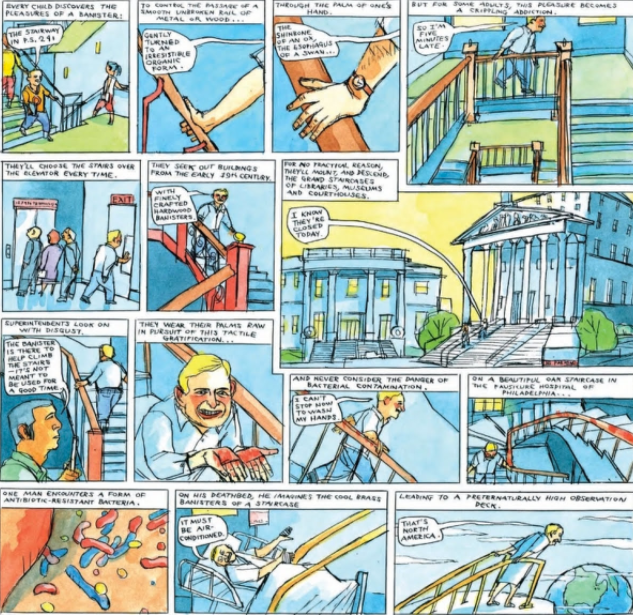

The next time I saw him, he had a simple answer to that question: He had more control over the way the panels looked, and in his opinion, the strip was better. The move wasn’t about speed, he said; because the pictures could be easily changed, he probably spent more time revising them. I wasn’t swayed, until I talked with him recently on the occasion of the republication of his debut 1991 graphic novel, Cheap Novelties: The Pleasures of Urban Decay (Drawn & Quarterly). For him, art tools aren’t things to be fetishized; if anything, they are antithetical to the comic strip’s appeal as a story for the masses, rather than a work of art for the privileged few.

Here, Ben talks more about the beauty of mass reproduction, waiting for chance inspiration, and the difference between creativity and craft.

Early encouragement

I’ve been making comic strips since I was a child. It was just a feeling that I wanted to make a kind of comic strip that I couldn’t find anywhere. I remember that impulse. I said, “I wish there were a comic strip that felt like it was written by my favorite writer and drawn by my favorite painter.” And I said, “That doesn’t exist.” So I had to make it.

When I was in junior high school, I took a life drawing class at the Brooklyn Museum with this painter named Andy Reiss. I didn’t know anything about the history of Western figure drawing, so that was a big thing for him to show me. For someone who knew nothing, anything he showed me was sort of a revelation. But he showed me really wonderful things. That’s all a teacher has to do: Point you in some direction that’s very fruitful. And he didn’t discourage me from doing comics. He could have said, “Why do you want to do this business?” but he didn’t; he appreciated comics, even though, in those days, comics were not considered a very valid art form.

My father was a big influence on me — his politics and his view of the world coming from Poland before the Second World War as a socialist. He made me pretty cynical about things, even of having a career. And he supported my making pictures; he thought it was worth doing, not a completely frivolous thing to do. A lot of friends of mine had parents who thought they were crazy for wanting to draw. Everybody in my generation, the kids who I grew up with, aimed to be a doctor or in science. That was what middle-class people wanted their children to do.

The rare privilege of creative work

I was very lucky to do comics at the tail end of the newspaper world and the publishing industry, when you could sort of eke out a living. Without an audience, I think it would be very hard to want to do anything like make comic strips or write a book. It’s too hard. When people don’t have an audience, they’re missing that last impulse, that last push to make something, because nobody’s waiting for it.

It feels like a miracle of cultural timing if you can have a career making comics, so what more could I need? If I did anything differently, I would not have ended up doing what I did. I would have been sidetracked. I led a very unadventurous life in a way — just tried to do this work. If I did anything more adventurous, it would have derailed everything.

If you do any kind of work that vaguely involves having some creative inspiration, that’s a rare job. Most jobs don’t call for creativity, and most people aren’t going to be asked to be creative or to shake things up. Most people are just frustrated, I think, because nobody wants their ideas. The real question is how to live with creativity being stifled. How do you not shoot somebody, go crazy? People in advertising talk about creativity, but they’re just coming up with gimmicks. If they were creative, they would rethink the market economy.

Learning a trade

I don’t like to have too much of a routine other than I try not to get up early. If I haven’t died that night, I get up — I’m happy to wake up — and have breakfast. It’s very easy to avoid working. When I don’t have a pressing deadline, I have to do all kinds of other things — look at things, go for walks. So that’s probably my routine: putting things off. I’m not putting the work off because I don’t want to do it. I’m just hoping to come up with a better story, and it’s hard to make that happen automatically. It happens by chance.

In a good strip, there should be some rethinking of the subject matter, and that’s difficult to orchestrate. I always know when it happens, like when I have this strip that isn’t going anywhere, and then I go downstairs to pick up the mail, and in the elevator it suddenly hits me — this angle or solution. But that’s only because I’ve been agonizing over it all week. If it doesn’t come, I’ll still have a strip; it just might not be one of the better ones.

I know people like to ask about what kind of pen I use, what kind of paper, like there’s a secret to this. I tell them, “You can sit at my table with the same pen and paper, and it’s not going to help you, because you didn’t work at figure drawing and storytelling for years.” You build up these skills. Just like somebody who makes chairs is more likely to make a great chair. When you do anything in a serial production, there are just these micro seconds of creativity, then the rest of it is just the craft of making the thing. There’s the workmanlike approach where you just say, “Here’s this thing I want to demonstrate.” I’ve practiced drawing for decades and know how to use language in some limited way, and I can put these together and make this plausible story or demonstration.

I think people should have more skills and trades. They’d realize in doing something like learning how to bake or make furniture, there are these moments of very high creativity. In France, people who can build a cabinet or refinish an old armoire are considered to have really valuable skills. Here, I don’t think people value those things much. Maybe they want to invent some kind of app or financial instrument.

It’s not possible for me to have a creative block. I just make the thing, and then it’s agony because I never think it’s that good. If I’m lucky, I think of something at the last minute that might save it — some new angle on this subject or a subject that people have never bothered to write about because they thought it was below their notice or something.

The pleasures of digital production

I know a lot of painters get into the pleasure of smearing paint around, but that’s not my interest in picture making. I don’t think of making pictures as this fun activity. It’s just kind of the other end of the spectrum of writing. It’s agony.

I mainly draw digitally now. My desk is a Cintiq, a big glass drawing board. I have a portable one, too. I could work anywhere. I’ve drawn in hotel rooms, on ships, crossing the ocean. I don’t use vector graphics; my strips are all just bitmap drawings. There is no original, which is great. I feel like it’s more like being a filmmaker, just making this image that has no material basis. But it’s still my handwriting, which is all I care about. My line, I think, is what’s important. And these digital styluses may be more sensitive than a pen. It’s a good interface between my hand and the digital realm.

I don’t sell my strips. Nobody really pays enough for a strip to make it worth selling. They wouldn’t even pay what I’m paid for one-time reproduction rights. I just keep the work together like a manuscript. Mostly people just cut the strip out of the magazine and tape it to their refrigerator door, so why would they want to buy it? But if they want a big one, something with more presence on the wall, I make digital prints. I really encourage people not to think about original art — the idea of these rare objects. That’s why I gravitated toward comics. I could have been a painter, and I said no. I hate the idea of making these single objects that somebody’s going to own and that no one else can see. I like mass reproduction, so everybody can have this thing in their life as a print or in a book.

The soundtrack

I only listen to music when I’m drawing; I can’t when I’m writing, because I have to hear the sound of the text. But when I draw, the reason it’s good to listen to music is that I use headphones or earplugs, which keeps me from getting up and stopping work. I do it to keep myself anchored to the drawing screen. I listen to an anarchist French chanteur named Léo Ferré, as well as Charles Aznavour and Jacques Brel. I like the songs of Charles Ives. I tend not to listen to orchestral music but more music and word combinations.

Inspiration

I was inspired by certain 18th-century, early 19th-century painters and English caricature artists like Thomas Rowlandson, George Cruikshank, James Gillray. Also, Poussin—a philosopher/painter—was a great influence. These people invented these text-image forms. They had this completely open field, it seemed. Some of them made sequential things, but they weren’t making comic strips, mainly single-panel cartoons or serial drawings. But the spatial drama in the things and the object description are just great.

I like scenes of cities in Italian realist films, like early Fellini, when you could shoot a film in a real location and nobody seemed to notice what you were doing. There’s minimal show business; the city is the theater. I also like those early films when they built these little fake cities in studios. It’s complete artifice. My strip is more like that. It’s like a tabletop train setup. It literally is like a miniature city built by a hobbyist. I’m too lazy to build them; I just draw them.